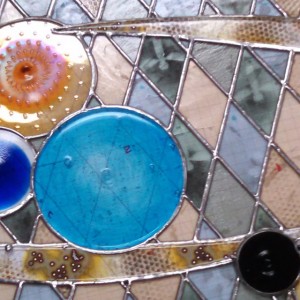

When I wake up in the morning, I think of myself as a scientist and a craftsman before seeing myself as an artist. For the 2015 Junior League Showhouse, I wanted to utilize my years of study of the chemistry of glass to push the limits of stained glass design through that lens. Many of the pieces in the background had glass powder applied and fused onto the surface, creating permanent imagery which will never lose its vibrancy. In the double helixes twisting across the two windows, precious metals were used to create reactions with the specific chemistry of that glass; in the heat of the kiln the metals fumed across the glass surface to create specific coloration which can be achieved no other way. Rondels made both in the kiln and via more traditional glassblowing methods give the piece its ultimate cohesiveness.

My favorite projects start with “Is it possible…?” I hope that looking at these windows, you consider conquering the same questions.

Glasswork is an incredibly technical process in which detail is king. Long hours are required for each repetitive process to yeild the result you see in “Heli-lens” (pronounced as if you have combined the words ‘helix’ & ‘lens’).

For the background harlequin grid, each piece was first cut and ground. Then in many cases, ground glass powders were lightly sifted and carefully pulled across the glass surface to create subtle imagery. To make that imagery permanent, those pieces would then be fired and annealed in a kiln, a 26 hour process which only accommodated a few dozen pieces at a time. Glass powders are considered very dangerous to work with and thus requires that the artist wear a respirator and protective clothing to prevent inhaling any particles.

The helixes had several layers of stacked glass sheets and also involved the use of fine silver metal, copper, sulfur & selenium to achieve the colored fuming across the surface. These metals react when heated (also in the kiln) at approximately 1450 degrees Fahrenheit.

The rondels were made both in the kiln and via more traditional glassblowing methods. At the furnace, a glassblower gathers molten glass at 3200 degrees Farenheit, applies color, and then goes through a repetitive process of reheating, smashing, twisting, and reheating until the pieces has spun out to his desired thickness and diameter with all of his desired elements included. The piece must then be annealed in a kiln overnight.

In the kiln, the artist must suspend a crucible of glass with a hole in the bottom. When heated to 1550 degrees, the glass slowly falls through the hole in the bottom of the crucible, possibly (hopefully) twisting and pulling against itself because of the different densities of the very chemical makeup of the different sheets of glass being heated. As they reach the kiln shelf below, the warm glass pools and creeps across like surface much like thick honey. The weight of glass initially packed in the crucible determines the size and shape of the final rondel achieved after the kiln anneals the piece and finishes cooling down.

Now all the pieces are made, the panels must be leaded together! In this case, each piece is individually wrapped with adhesive copper foil, then fluxed and soldered. While this is possibly the most straightforward part of the process, it is no less time consuming, in this case, over 20 hours were needed to foil, and another 16 spent soldering.

Believe it or not, much of this technique is nothing new. Artists have been using these same basic materials and processes for centuries. It is today’s science which gives it all such a new twist.

Enjoy.

With gratitude,

McElf

The end result of all this labor was absolutely spectacular. The windows are magnificent. Interesting to hear about the science and process behind the creation of this art glass.