à la Peacock

Materials: Glass, Copper, Silver, Lead, Zinc, Maple wood

Framing by Against the Grain Studio

Built in 2016 and now in a private residence in South Carolina.

Who doesn’t love the peacock?

Who doesn’t love the peacock?

The first time I ever really considered these strange birds at any length was on a college trip to study in London. I was awe-struck at the number of birds on royal property, and it was my very first time ever seeing white peacocks. Not only was I struck by how oh-my-geese-over-the-top-ostentatious these birds were, I was shocked at their insolence. “Not everything that glitters is gold…” indeed!

I’d been exposed to the haughty fowl before – they’re a complete nuisance in Miami having completely overrun quite a few Southern Florida communities! An article that ran in the NYTimes in 2008 read: “Roaming freely in packs of nearly a dozen, they shake their rumps like teenagers, dropping guano on $60,000 sedans and squawking with a sound akin to the screams of someone being attacked.” I hadn’t remembered them being so strikingly beautiful in Miami, however. And on my return, I visually confirmed that the Southern US Peninsula’s version of the showy bird was in fact much drabber!

I loved to watch birds with my Grandfather – Pops – and we often teased the mighty Peacock and all his plumage. But clearly, there’s an implicit challenge in that plumage more than a passing fancy: originally from India, they were always a symbol of royalty in their homeland and have been a favorite form in ornamentation for over a millennium. Peacocks were even being used on tombs of early Christians! It’s amazing how long the history of the peacock truly stretches back into the history of art.

I guess at the end of the day, I just wanted my own go.

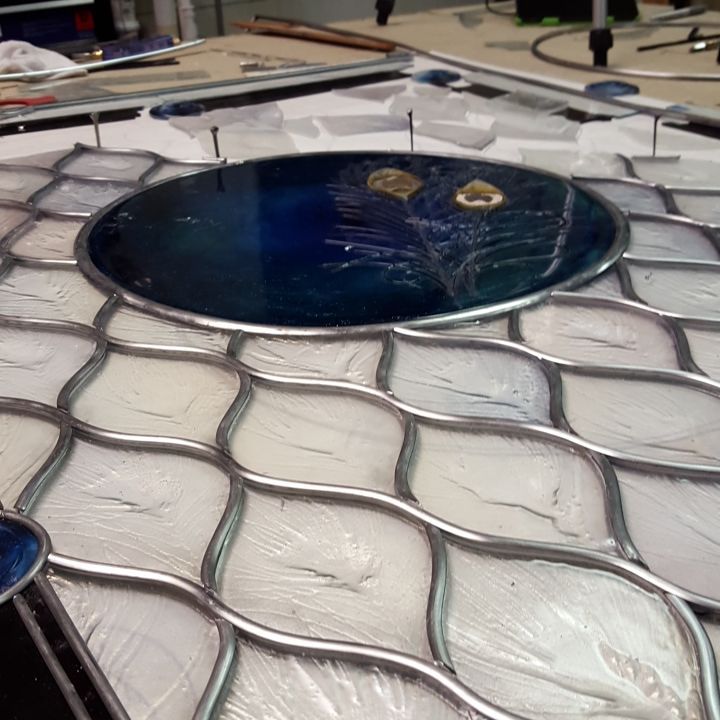

Each piece in the background was fired over a mold taken from an actual peacock feather. It took many, many failures before I honed the right firing schedule and molds. Only 6-9 pieces could be fired at a time, so it was many, many nights before I had enough pieces for construction. The small ~2” roundels in the border were carved in clay, then a mold was taken of that carving, and pre-fired blanks were cast into the mold. I was able to make two molds from my carving so that I could fire two pieces at a time.

In the meantime, I cast the central rondel one night in the kiln, using almost 3000 grams of glass to form the 15” round plate. Next, I used a vitrigraph kiln to create the stringers for the feather. This process is fairly simple, albeit time-consuming: a small kiln with a hole drilled in the bottom is mounted about 6’ high. Then, a crucible (also with a hole drilled in the bottom) is loaded with glass chunks and heated to 1700ºF. At this temperature, the glass begins to melt through the holes and out of the bottom of the kiln. Using this method, one can achieve organic, seamless curves in amazing lengths.

At the top of each feather, I formed wafers from glass powders and silver mesh to be the accents within the feather. Once all these individual elements of the feathers had been created, they were carefully assembled and fired onto the 15” rondel.

Finally, all the elements were ground to fit together and leaded together into one large piece. What made leading this piece interesting is that because the background piece were slumped over the feather molds, they had to be fit to each other not just side to side, but also up to down! The lead had to be carefully stretched and molded and formed to accommodate and huge amount of movement within each individual piece.

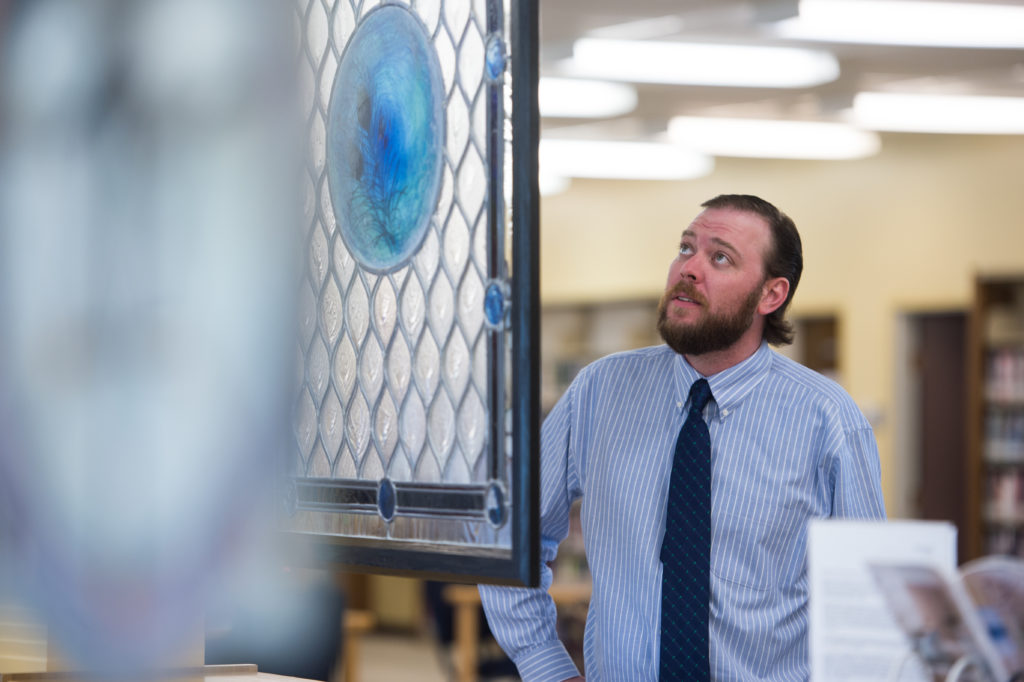

At this size, strength and reinforcement must be considered and the framing takes that into account while also continuing the decorative elements of the piece.

To finish the piece, small white peacock sculptures were cut, ground, foiled with copper, and soldering onto the piece after framing was complete.

All in all, over 30 kiln firings and 175+ hours went into this piece of work over the course of what could likely have been 4-6 months… but ended up being about 2 years. Keeping that amount of energy going into the same piece for that period of time might have been the greatest technical test of all!

Leave a Reply